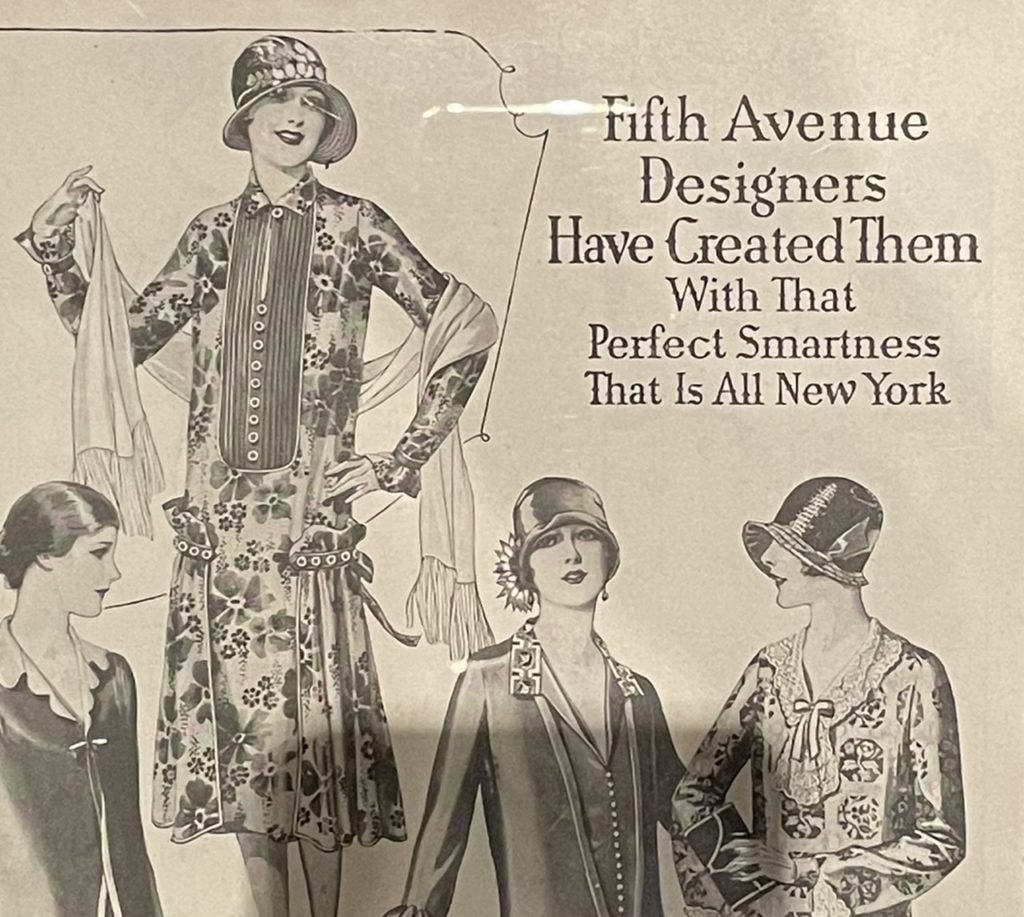

This artifact, likely a brooch, depicts a 1920s-era flapper, cloche hat and all. It was found at an archaeological site in Jersey City, New Jersey. This and the many other artifacts found during excavation of a series of former houses, most demolished by the 1930s, provide a glimpse of the middle class families who lived in Jersey City in the early twentieth century.

Reference:

Howson, Jean, and Leonard G. Bianchi

2014 Covert-Larch: Archaeology of a Jersey City Neighborhood: Data Recovery for the Route 1&9T (25) St. Paul’s Viaduct Replacement Project Jersey City, Hudson County, NJ, Volume 1. Cultural Resource Unit, The RBA Group, Inc.