Dam archaeology in New Jersey: 1970s archaeology along Assunpink Creek, and modern creek daylighting efforts in Trenton: Assunpink Creek Dam Site 20

Category: Archaeology

Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger) from a Nineteenth Century Archaeological Site in New Jersey

There are no confirmed historic records of fox squirrel from New Jersey, although it is present in surrounding states. One subspecies, the Delmarva fox squirrel, was recently removed from the endangered species list after a concerted effort was made in Delaware and neighboring states to help it.

While fox squirrel bones are found in zooarchaeological assemblages in other states, there is, only prehistoric archaeological site in New Jersey where fox squirrel has been identified. In this article (with a 2012 date, but only recently published), the first archaeological record of fox squirrel bones from a nineteenth century archaeological site in New Jersey is reported.

Archaeology on the Pastoral Islands of Lake Champlain

Suzanne Carmick writes in the New York Times Travel Section about visiting the Pastoral Islands of Lake Champlain. The Vermont islands of South Hero, North Hero, and Isle La Motte, are on the border of New York and just south of Canada.

Carmick mentions the long history of Isle La Motte, which was occupied by Native Americans long before Samuel Champlain first recorded it in 1609. In A.D. 1666, the French built Fort St. Anne on Isle La Motte. The fort was occupied for as little as two years before being abandoned. In the late 1800s, the Catholic Church purchased the land, which became St. Anne’s Shrine. A Vermont priest, Father Joseph Kerlidou excavated the remains of the French fort.

In 1917, archaeologist Warren Moorehead conducted excavations near the shrine, finding Woodland period ceramics. At another location, Reynolds Point, he found artifacts from the earlier Archaic period. In the early 1960s, a cremation burial site attributed to the Archaic Glacial Kame culture was accidentally uncovered by workers on the island. New York State Archaeologist William Ritchie examined the artifacts found with the ochre-stained human bones. The grave goods included Native copper adzes, copper beads, shell gorgets and beads, and over 100 pieces of galena.

For more on Fort St. Anne, see Enshrining the Past: The Early Archaeology of Fort St. Anne, Isle La Motte, Vermont

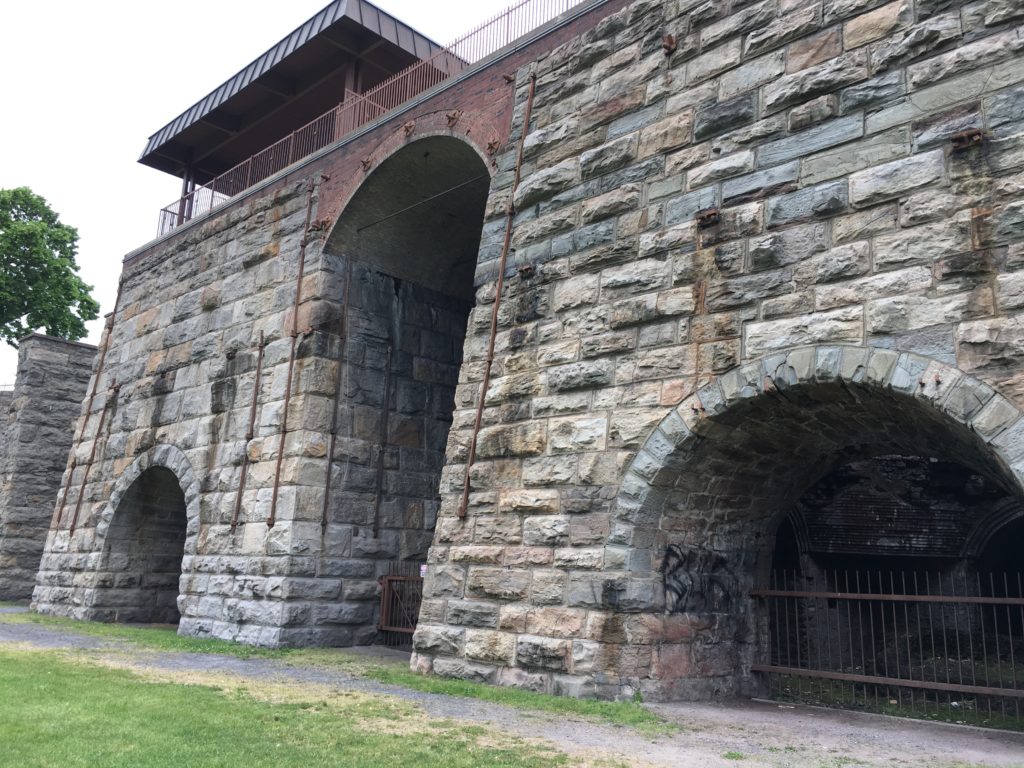

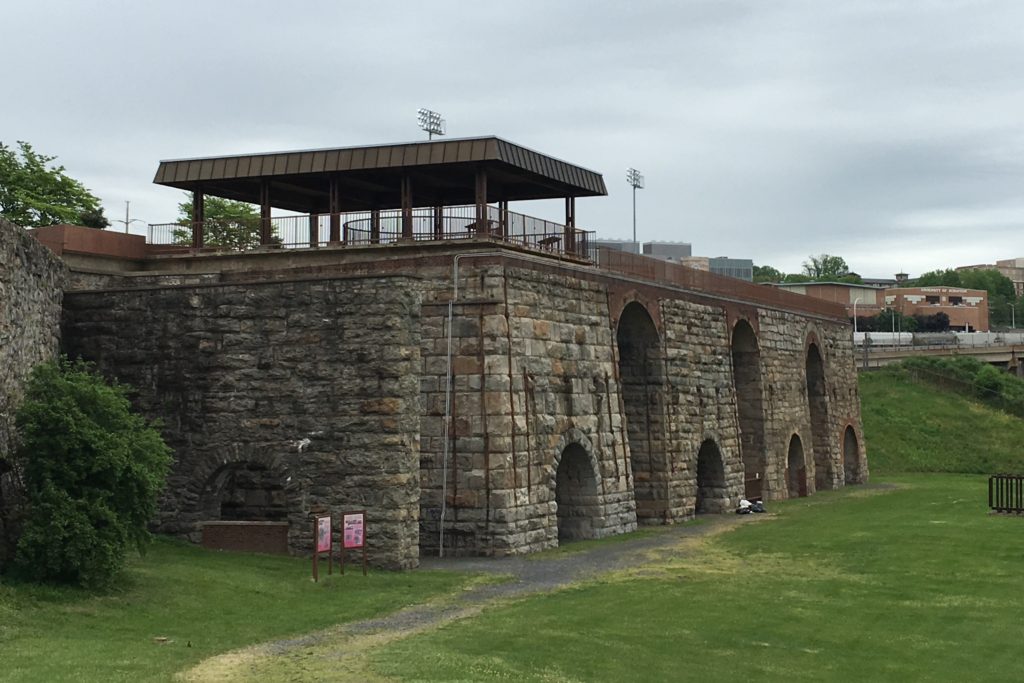

Blast Furnaces at Scranton, Pennsylvania

The stone blast furnaces in a park just outside of downtown Scranton are an imposing reminder of this Pennsylvania city’s early industrial history. George and Selden Scranton had owned an iron furnace in northern New Jersey before moving to Pennsylvania. In 1840, they and their partners built an iron furnace in Slocum Hollow on the Roaring Brook. Their enterprise, later renamed the Lackawanna Iron and Steel Company, grew to become one of the largest producers of iron in the United States. At the turn of the twentieth century, however, the company moved its operations to New York. The mills and other buildings were demolished, leaving only the four blast furnaces behind.

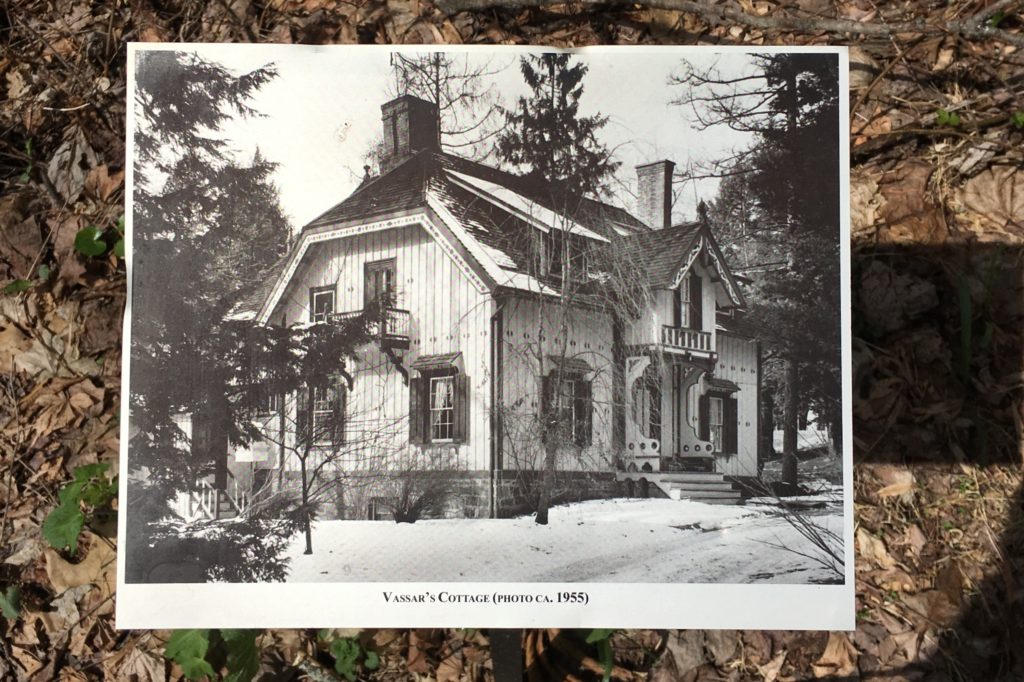

The Landscape A.J. Downing Designed at Springside, New York

Springside is a nineteenth-century park and estate built by Matthew Vassar in Poughkeepsie, New York that is now maintained by a non-profit organization and is open to the public.

Vassar, who made his fortune in brewing beer before founding the women’s college that bears his name, bought 43 acres of land on the south side of Poughkeepsie in 1850 and hired famed landscape gardener Andrew Jackson Downing and his architect partner, Calvert Vaux, to design a summer estate for him.

Although Downing died in 1852 in a fire on a Hudson River steamship, Vaux and Vassar continued to work on Springside. Vassar moved into the cottage built on the site; a larger villa was planned, but never constructed, as Vassar preferred the smaller cottage. Vassar lived at Springside fulltime beginning in 1867.

After his death, the property passed on to a series of owners, and was subdivided and merged with other properties, but most of the buildings and the constructed landscape survived mostly intact. In the twentieth century, Springside faced a series of threats from development. In 1969, Springside was listed as a National Historic Landmark, but within weeks, the barn and carriage house were burned down by arsonists. In 1970, the property was sold to a developer. In 1976, the cottage was in danger of destruction. The façade of the cottage was removed to the New York State Museum, and the rest of the cottage was destroyed. In the 1980s, under threat of a lawsuit from preservationists, an agreement was reached to preserve about half of the estate and allow the construction of condominiums on the other half.

Springside is now maintained by a nonprofit organization, Springside Landscape Restoration. Now, most of the pathways have been cleared and they curve among the rocky knolls. The original Beautiful and Picturesque landscape now tends more towards the picturesque, with tangled, unkempt plants held partially in check along the pathways.

The Name of the Sword

Glamdring, Andúril, Sting. Some weapons have names. Beowulf used the sword Hrunting, King Arthur had Excalibur, and of course the hammer of Thor is Mjölnir. In The Spirit of the Sword and Spear (Cambridge Archaeological Journal 23(1):55-67), Mark Pearce references the named weapons of myth and history to argue that swords and spears can have individual identities, and thus, potentially, biographies. As he says, “I do not mean to argue that prehistoric weapons were regarded as equivalent to humans, but rather that they had some sort of spiritual persona…with its own specific agency, believed to have its own intention and volition. This might have been perceived as some sort of in-dwelling spirit.” (p. 55)

From these named weapons, he attempts to look farther back in time to ascertain whether swords and other weapons from the Iron Age of Europe also were assigned identities. There are, in fact, at least two Iron Age swords with names stamped onto their blades, although the names could belong to the sword, the owner, or the blacksmith.

More common are swords and spears that have faces (or geometric designs that could be interpreted as faces), which, Pearce argues, may also indicate that they were given an identity. He is aware that “It is dangerous to use analogies from myth to reconstruct prehistoric reality” (p. 64) and “it is certainly true that human beings have a tendency to interpret unstructured visual stimuli in meaningful ways” and “It might be easy to over-interpret stimuli that may seem to depict faces.” (p. 62)

Against these statements, he can muster only a weak defense: “But when looking at the spearheads and swords illustrated in this article, the faces are very striking… It is clearly impossible to demonstrate conclusively that faces are meant, but it does seem evident.” (p. 62)

It does not help that “in some cases the decoration tends towards the abstract and can be recognized as indicating a face only by reference to, and comparison with, the more figurative examples.” (p. 62)

Yet his main idea is intriguing. Perhaps a less descriptive and more analytical approach would produce stronger results.

The article is open access and available to download at the Cambridge Archaeological Journal.

originally posted on Adequacy (2013)

Reference:

The Late Archaic Site by the Parking Garage: More on Coralville, Iowa

The redevelopment of that Coralville, Iowa wetland park/restaurant/hotel complex uncovered a prehistoric archaeological site officially known as the Edgewater Park Site (13JH1132). The initial survey by archaeologists prior to construction discovered that artifacts were present about one meter below the ground surface. Therefore, the upper meter of soil was removed over a 10 x 10 meter area (near the current parking garage) to expose the artifact-bearing layers.

The dig recovered about 15,000 artifacts. Most of these are stone flakes, but there are also 17 projectile points. Ten of these are Table Rock points, a side-notched biface similar to the widespread Late Archaic Durst, Dustin, and Lamoka points found elsewhere. The only other diagnostic point is a Stone Square Stemmed point that also dates to the Late Archaic.

Concentrations of fire-cracked rock likely are the remains of several hearths, and the distribution of the stone debitage (primarily Maynes Creek chert, which is found naturally about 100km away from the site) may reveal areas where individuals were creating stone tools between 3,500 and 3,900 years ago. Three types of plants found at the site, barnyard grass, little barley, and knotweed, could possibly have been cultivated there. Archaeologists think that the Edgewater Park site was a warm-weather camp temporarily used by hunter-gatherers who may have also been beginning to use domesticated plants.

The Office of the State Archaeologist of Iowa has more information on the Edgewater Park Site, and photos of the excavation can be seen on Flickr.

Reference:

William E. Whittaker, Michael T. Dunne, Joe Alan Artz, Sarah E. Horgen and Mark L. Anderson

2007 Edgewater Park: A Late Archaic Campsite along the Iowa River. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 32 (1):5-45.

Early Hominins and Meat-Eating

Comprehensive review article on use of meat by early hominins from The American Scientist.

The Skeleton Revealed

Fascinating-looking book by Steve Huskey of animal skeletons in dynamic poses. Lots of photos at the Nature Conservancy site.

Banded Slate Bannerstone

An attractive, if poorly provenienced, banded slate bannerstone from Michigan. Ralph T. Coe Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art.