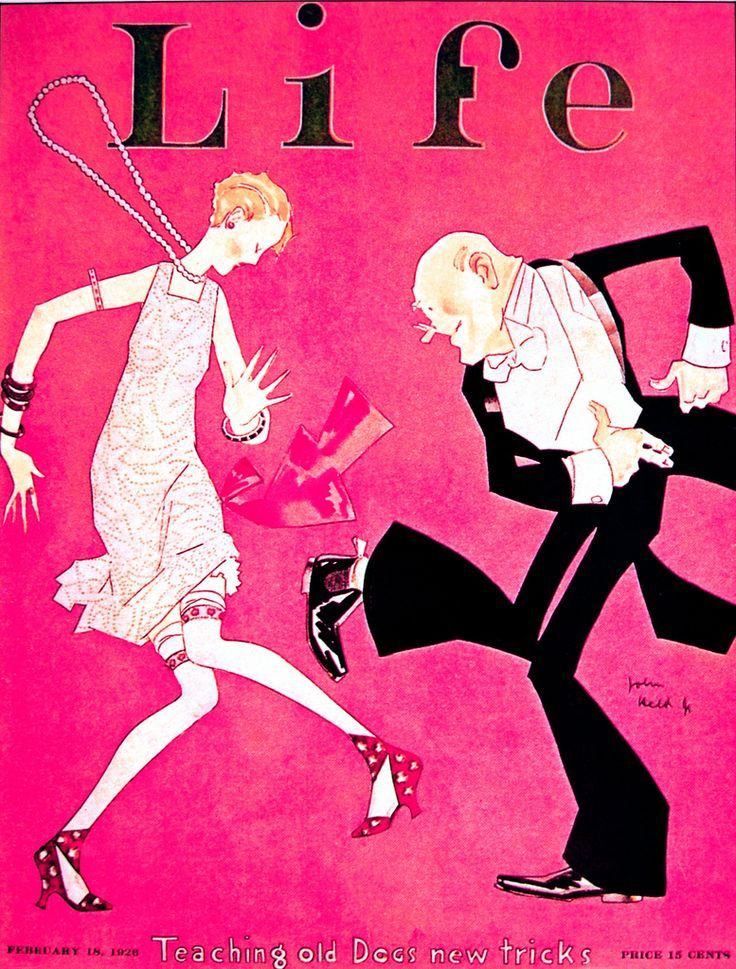

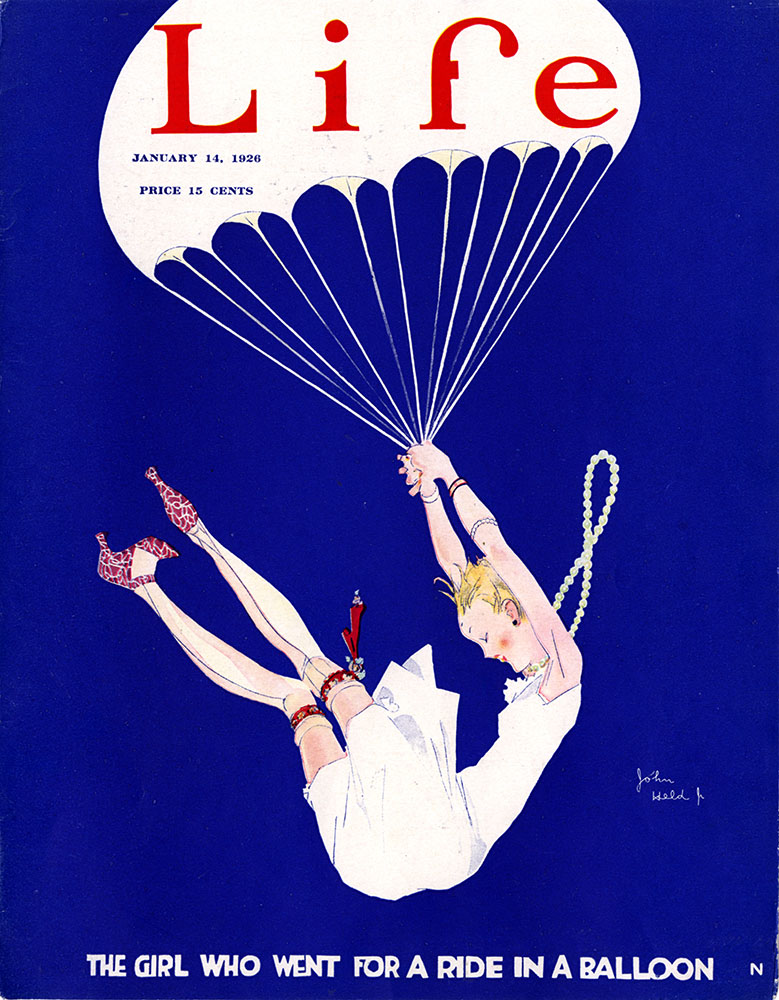

In the 1920s, John Held, Jr., became famous for his drawings in Life, Vanity Fair, and other magazines that enshrined the iconic flapper image: lean and leggy, with beaded necklace swinging as she danced the Charleston with her companion, the round-headed, pencil-necked, Joe College.

The “tall, dark and tweedy” (Shuttleworth 1965) artist had come to New York City from Utah in 1912, where he found work as a commercial artist. As America entered World War I, John Held would take on another, clandestine, responsibility.Held had become interested in Mayan art, and through a sculptor friend who worked at the American Museum of Natural History, he met first the curator Herbert Spinden, and then archaeologist Sylvanus Morley, who hired him as the staff artist for an archaeological expedition to Central America.

Morley was also working for U.S. Naval Intelligence, tasked with recruiting other anthropologists to report on German activities in Central America. Held, known as Agent 154, was one of the first to be recruited. Morley paid Held $50 a month for his work as an archaeological illustrator; the Office of Naval Intelligence kicked in another $100 a month, plus a $4 per diem, for his spywork. Morley kitted out the expedition with gear from Abercrombie & Fitch, and he and Held traveled throughout Central America, including much of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, in search of German intrigue and secret U-boat bases (there was little of the former and none of the latter), while also finding time to conduct some actual archaeological reconnaissance at the site of Copan.

The two spies often traveled by mule. Years later, when Held owned a working farm, he had two mules of his own. He named them Abercrombie and Fitch.

After the expedition, Held returned to New York. In the Roaring Twenties, his magazine covers, cartoons, and advertising art caught the zeitgeist of the times and made him a millionaire. When a friend from Utah, Harold Ross, cofounded the New Yorker magazine in 1925, Held contributed a series of linoleum cut cartoons that recalled the old-fashioned Gay Nineties era of his childhood.

As the Jazz Age ended, so did his fame, and he lost much of his money during the Great Depression. He continued to produce art and books, but his flappers were now out of style.

Held would later work for the U.S. Signal Corps at Camp Evans, where he and his fourth wife (also an artist), worked on another top secret project, drawing blueprints for radar technology used during World War II. They settled down on a farm near Belmar, New Jersey, where John Held, Jr. passed away in 1958.

Selected References:

Blackwell, Jon

2001 Artist held an era’s attention. Asbury Park Press/InfoAge Museum.

Browman, David

2011 Spying by American Archaeologists in World War I (with a minor linkage to the development of the Society for American Archaeology). Bulletin of the History of Archaeology 21 (2):10-17.

Harris, Charles H., and Louis R. Sadler

2009 The Archaeologist was a Spy: Sylvanus G. Morley and the Office of Naval Intelligence. University of New Mexico Press.

MGHL Staff

2014 Happy Birthday John Held Jr.

Pezzati, Alex

2003 Held in the Archives: Famous Jazz Age Artist’s Watercolors in UPM’s Archives. Expedition 45:3

Shuttleworth, Jack

1965 John Held, Jr., and his World. American Heritage. 16:5.