Megafauna skeletons on display at the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport (CVG), just south of the Ohio River in Boone County, Kentucky). The famous paleontological site, Big Bone Lick, is only about 20 miles south of the airport.

You begin to interest me…vaguely

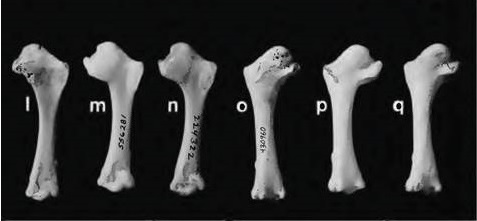

From the Smithsonian Institution, here’s a passenger pigeon bone, specifically a left humerus (wing). the Smithsonian only identifies it as being from Bartow County, Georgia, but given the collector is attributed to “Lipps et al,” it is likely from Ladd’s Quarry. In the 1960s, Shorter College biology professor Emma Lewis Lipps excavated at this site and sent many fossils to the Smithsonian.

In 1858, William Parker Foulke was shown some large bones that had been dug out of a marl pit in Haddonfield, New Jersey, two decades earlier. Foulke and Joseph Leidy then dug up more bones from the site and named the dinosaur Hadrosaurus foulkii. Some earlier, more fragmented dinosaur remains had been found earlier in the nineteenth century, but Hadrosaurus was the first more or less complete dinosaur skeleton.

The original dig site is now in a park in Haddonfield. A plaque, interpretive sign, and a picnic table with toy dinosaurs you can play with commemorate the find. A statue of Hadrosaurus can be found a few minutes away in downtown Haddonfield.

Book review of Donald K. Grayson’s Giant Sloths and Sabertooth Cats: Extinct Mammals and the Archaeology of the Ice Age Great Basin is now available here.

Publisher Taylor & Francis is offering free access to all 2013 and 2014 articles from 17 Paleontology and Earth Science journals to celebrate both National Fossil Day and the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology and the Geological Society of America annual meetings. Articles will be available for free through the end of 2015.

The ten journals are:

Alcheringa

Australian Journal of Earth Sciences

Geodesy and Cartography

GFF (Geological Society of Sweden)

Geodinamica Acta

Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk

Grana

Historical Biology

Ichnos

International Geology Review

Journal of Earthquake Engineering

Journal of Systematic Palaeontology

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology

Marine Georesources & Geotechnology

New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics

Palynology

Rocks and Minerals

Access the journals here:

How old is the earliest passenger pigeon fossil? A single wing bone found at the Lee Creek Mine paleontological locality in North Carolina is 3.7 to 4.8 million years old, a time period known as the Early Pliocene. It is reasonable to ask whether a fossil that old is from the same species as the historically known passenger pigeon, and the paleontologists who identified it were cautious, officially labeling the humerus bone Ectopistes aff. migratorius, but also stating that “Apart from the slightly larger size, which probably would have been encompassed by variation in the recent species, the fossil shows no distinguishing differences from E. migratorius.” (Olson and Rasmussen 2001:300).

The thousands of other fossil bird bones found here were originally deposited in deep marine water and in fact most of the identified birds are ocean-going species like auks, shearwaters, and albatrosses. Land based birds (including the passenger pigeon) comprise a very small proportion of the assemblage (Olson and Rasmussen 2001).

Reference:

Olson, Storrs L., and Pamela C. Rasmussen

2001 Miocene and Pliocene birds from the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 90:233-365.

A controversial dam and reservoir planned for British Columbia, Canada, is expected to flood over 12,000 acres (5000 hectares) of land in the Peace River valley. The Peace River Valley is home to Charlie Lake Cave (also known as Tse’K’wa), where archaeologist Jonathan Driver identified what may be the northernmost passenger pigeon fossils ever found. Charlie Lake Cave is just north of 56° latitude on the eastern side of the Canadian Rockies. Passenger pigeon bones were found in a level dated between 9,000-8,100 years ago, as well as in younger deposits.

While this site is not directly threatened by the Site C dam, hundreds of other archaeological and paleontological sites will be flooded by the BC Hydro project. Local First Nation tribes and other residents are also opposed to the project.

For more information, see The Globe and Mail story.

For more on Charlie Lake Cave, including video interviews with Jon Driver, check out A Journey to a New Land, created by the Simon Fraser University Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology

Reference:

Driver, Jonathan C., and Keith A. Hobson

1992 A 10 500-year sequence of bird remains from the Southern Boreal Forest region of western Canada. Arctic 45(2):105-110.

One more quote from paleontologist Clayton E. Ray, this time on the epistemology of identifying animal bones:

“… the techniques [of comparative methodology, i.e., comparing unknowns to knowns] were not codified and universally applied until the nineteenth century under the influence of Cuvier, Owen, and Agassiz. This could not have occurred prior to the Age of Enlightenment/Reason, with the spread of the notion that all problems could be successfully solved through intensive inspection and that ordinary humans could rely on their own careful observations irrespective of authority.[emphasis added] … Until recently, this reliance was taken for granted, so much so that the sublime notion could be expressed profanely, if I may be permitted one homely example: Remington Kellogg, once asked by a colleague what criteria allowed him to conclude that a certain fragmentary whale vertebra was in fact identifiable to a particular species, immediately replied resoundingly, “because it looks like it, goddamit it!” He did not live to experience the postmodern entry of doubt introduced by phylogenetic systematics and social constructivism, in which we question the meaning of all our observations.” (p.7)

More from Clayton E. Ray:

discoveries do not stay discovered; they must be tended like a garden. (p. 15)

approach to truth is a fragile dynamic that requires continual vigilance. There may be some validity to Gould’s (1996:110) claim that “persistent minor errors of pure ignorance are galling to perfectionistic professionals,” but this has no bearing on the overriding requirement that each professional strive assiduously to get things right and never knowingly let even “minor errors” persist.(p. 16)

Reference:

Clayton E. Ray 2001. Prodromus. In Geology and Paleontology of the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina, III. Edited by C.E. Ray and D.J. Bohaska. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology, number 90:1-20.

I don’t think I have ever read an introduction to a collection of paleontology papers that had more gems than Clayton E. Ray’s “Prodomus” to a volume on Miocene/Pliocene Lee Creek Mine locality. Like this:

Having flattered myself that I had unearthed essentially everything, it is salutary to be reminded through several oversights that in antiquarian, as in paleontological, research one can never do too much digging. Returns in each are apt to be unpredictable and to be meager in relation to time invested (hardly “cost effective”), but there will always be something new, and, to comprehend it when found, one must be steeped in the subject. (p. 1)

Reference:

Clayton E. Ray 2001. Prodromus. In Geology and Paleontology of the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina, III. Edited by C.E. Ray and D.J. Bohaska. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology, number 90:1-20.