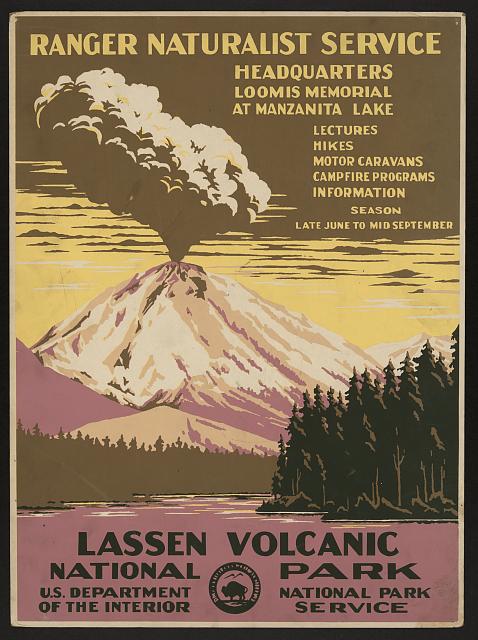

I just posted about WPA-era posters created for the U.S. National Parks. One of the great successes of the Depression-era New Deal was how it provided jobs for all Americans, including artists who created lasting works of art like these Post Office murals.

Another beneficiary was the Rutgers Geology Museum. In 1936, the Works Progress Administration funded 21 paintings for the museum by Alfred Poledo, a little-known 1930s artist. Like, there is almost nothing on the Internet about him. There’s this at the Living New Deal, which indicates he was from Boonton, and there’s some census data that shows he was an Italian immigrant, born around 1888 and deceased by 1940.

At least three of his paintings are in the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University. The mosasaur, an extinct marine reptile whose fossils are found in New Jersey, is featured in two of the pieces, A Lagoon in Jurassic Time and A New Jersey Mosasaur, both dated 1936.

The undated Prehistoric Animals Ready for Battle is the only one that shows dinosaurs. What I presume is a Dryptosaurus (a New Jersey dino related to Tyrannosaurus) faces off against a Triceratops, while some hadrosaurs (the official New Jersey state dinosaur) walk through the background.

These three paintings were donated to the Zimmerli by Helgi Johnson, a professor in the Geology Department who died in 1974. It’s not clear whether the other paintings in the series are also in the Zimmerli or perhaps still at the Geology Museum.