If you know anything about passenger pigeons, you know the last passenger pigeon was named Martha. She died 106 years ago today, on September 1st, 1914.

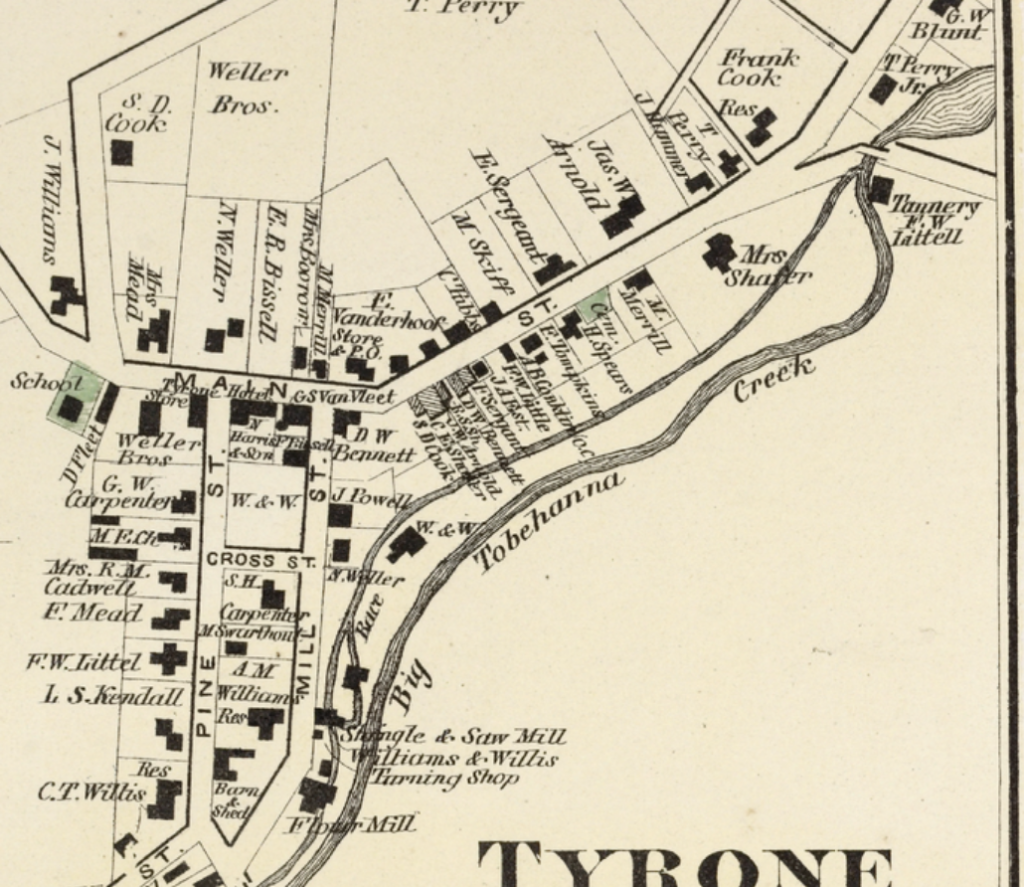

In 1977 the Cincinnati Zoo, where Martha lived and died, created a memorial to the extinct passenger pigeon in one of the few surviving original animal houses. The photo above shows part of the large wooden door covered with carvings of passenger pigeons at the entrance.

The pagoda-style building was built as an aviary to display many types of birds. It and two other animal houses that also date back to the zoo’s opening in 1875 have been designated a National Historic Landmark.

.jpg)

The creation of the memorial was due in large part to the efforts of Richard Fluke who, as a child, frequently visited Martha at the zoo.

“The world lost a great bird,” said Fluke, his voice still emotional at the memory, even after 74 years. “She was just magnificent. When [she died], I felt that I had lost a pal, because I always went around to see her.” Perhaps this is the greatest value of Richard Fluke’s testimony. Others mourned Martha’s loss — and still mourn it — in the abstract, as the point final in the tragic history of a species wasted through human greed. But the little boy who sat in the yellow pagoda, talking to her, stroking her feathers, feeding her tiny bits of food, mourned the passing of his friend.

T. F. Pawlick, Martha: The Last of Her Kind. 2018