A one-day conference focusing on the Archaeological Curation Crisis in the 21st Century will be held Saturday, April 23 at Marlboro College in Brattleboro, Vermont. The meeting is organized by the Conference on New England Archaeology. For more information, visit the CNEA .

Tag: museum

The Fluted Points in the File Folder

Before eminent archaeologist John Cotter passed away in 1999, he donated much of his personal library to his colleague Anthony Boldurian and the University of Pittsburgh at Greensburg. As they sorted through the books, file folders, and papers, they found something completely unexpected: a plastic sandwich bag with two neatly wrapped Clovis fluted points inside.

Cotter is best known as one of the pioneers of American historical archaeology, but he began his career studying Paleoindian archaeology, earning his M.A. in 1935. He had originally planned to write his dissertation on the Clovis material from Blackwater Draw, but by the time he returned to graduate studies at Penn in the 1950s, he had switched his subject to the excavations he had done at historic Jamestown, Virginia with the National Park Service. Yet he always maintained an interest in Paleoindian archaeology, and in fact his final publication, with Boldurian, was titled Clovis Revisited.

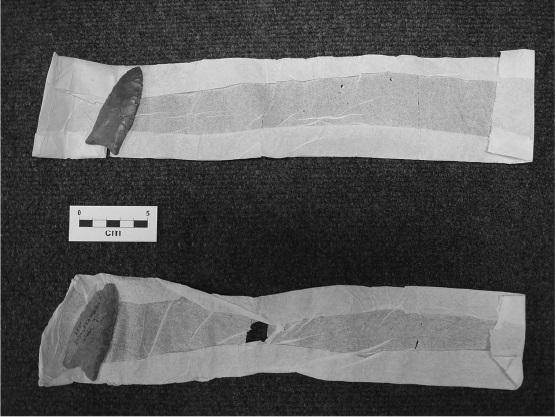

One of the points was labeled with his name and the location “Western Kentucky 1939.” At that time, Cotter was the state supervisor of the Archaeological Survey of Kentucky, and much of his time was spent examining the multiple excavations underway and ferrying supplies and artifacts to and from the laboratory, but there is no other contextual information for this point.

The second point is unlabeled, but made from a type of chert (Vera Cruz jasper) found in eastern Pennsylvania. The authors don’t say how difficult it was to figure this one out, but they matched this point to a photo of a fluted point found in New Jersey and published in one of the early articles on Paleoindian stone tools, Edgar B. Howard’s 1934 “Grooved Spearpoints.” That New Jersey point was in the collections of the University Museum at the University of Pennsylvania, where Cotter became a professor and curator. The authors found a drawing of the same Clovis point in the appendix of Cotter’s 1935 thesis.

The projectile point is part of the Newbold collection, accumulated by a New Jersey gentleman farmer in the second half of the nineteenth century. Michael Newbold would pay his workers as much as five cents for artifacts they found on his farm in Burlington County. After his death, the then-new University Museum acquired his collection – decades before anyone knew how old those fluted points were.

How did they end up among the paperwork? It seems likely Cotter was working with the specimens (he was particularly interested in a specific diagnostic characteristic, called basal polish or basal edge grinding, that both points have) in his office and at some point –perhaps even after his death– the bag holding them got bundled up with related articles and filed away in a bookshelf. It’s a nice example of lost artifacts being found again.

Reference:

Boldurian, Anthony T., Justin D. McKeel, and Mason G. Pickel

2012 Gifts from an archaeologist’s bookcase: John L. Cotter’s library. North American Archaeologist 33(2):193-237.

Indian Motorcycles at the American Swedish Museum

Why does the American Swedish Historical Museum have an exhibit on Indian motorcycles? Because one of the founders of the Indian Motorcycle Company, Carl Oscar Hedstrom, was an immigrant from Sweden. The museum, located in Philadelphia, has several motorcycles and other artifacts on display. While there, you can also pick up some herring and lingonberry preserves at the gift shop.

Passenger Pigeon Lecture at New York State Museum

Next month, the New York State Museum will be presenting a lecture on the passenger pigeon. Jeremy Kirchman is no stranger to extinct birds, having done research on the Carolina parakeet, the (possibly extinct) Ivory-billed Woodpecker, and others.

The passenger pigeon, icon of extinction

September 28, 2014 : 1:00 P.M. – 2:00 P.M.

Description: One hundred years ago, on September 1st 1914, the world’s last Passenger Pigeon died in captivity at the Cincinnati Zoo marking the demise of a species that once numbered in the billion of birds. What were Passenger Pigeons, and what happened to cause their extinction? Please join Dr. Jeremy Kirchman, New York State Museum Curator of Birds, as he presents this lecture on the life and times of America’s “wild pigeon”.

The Wagner Borrows a Passenger Pigeon

The Wagner Free Institute of Science in Philadelphia has many interesting things in its natural history collection, most still exhibited in their Victorian era display cabinets. But one thing they don’t have is a passenger pigeon. So they borrowed one from the nearby John Heinz at Tinicum National Wildlife Refuge. The mounted specimen will be on display at the Wagner until September 2014.

“quite a famously extinct species”

The Whanganui Regional Museum in New Zealand has three passenger pigeons in their collections, including this somewhat pale female donated to the museum in the nineteenth century by German ornithologist Otto Finsch.

Dr. Erich Dorfman, author of the quote above, described their specimens in this blog post.

New Passenger Pigeon Exhibit at Granville Museum

Looks like the Pember Museum in Granville, New York has a lovely new exhibit on the passenger pigeon. The museum, located near the Vermont border, has two mounted passenger pigeons and a clutch of eggs (a third specimen is on loan to the Adirondack Museum).

The Manchester Newspapers has just published an article by Derek Liebig on the exhibit, and you can also visit the museum’s website.

More Details of the Lamoka Diorama

Here’s a photo showing part of the interior of the house in the Lamoka diorama at the New York State Museum. The lodge itself is based on Ritchie’s interpretation of the numerous post molds and features he described as floors at the site, as detailed in his book The Archaeology of New York State. The contents of the interior of the lodge are more speculative. Some items are based on actual artifacts found at the site, like the antlers seen hanging from one of the wooden supports. Others are undoubtedly inferred from more recent Native Americans, ethnographic hunter-gatherers, and other archaeological evidence. The textiles in particular are beautifully done.

Here’s a photo showing part of the interior of the house in the Lamoka diorama at the New York State Museum. The lodge itself is based on Ritchie’s interpretation of the numerous post molds and features he described as floors at the site, as detailed in his book The Archaeology of New York State. The contents of the interior of the lodge are more speculative. Some items are based on actual artifacts found at the site, like the antlers seen hanging from one of the wooden supports. Others are undoubtedly inferred from more recent Native Americans, ethnographic hunter-gatherers, and other archaeological evidence. The textiles in particular are beautifully done.

Especially interesting is the bow seen hanging on the left side of the photo. Most archaeologists would probably doubt that bows and arrows were used during the Late Archaic in New York. Instead, atlatls (spear throwers) are considered the primary projectile weapon of the time (although bannerstones/atlatl weights are rare to nonexistent at Lamoka). The issue is unresolved however, and several archaeologists have argued for the presence of bows and arrows by this time period (see, for example, Evidence for Bow and Arrow Use in the Small Point Late Archaic of Southwestern Ontario

by Kristen Snarey and Christopher Ellis).

Recreating Lamoka at the New York State Museum

Always love seeing the life-size diorama of the Lamoka Lake site, representing the Archaic Period, at the New York State Museum in Albany. Based, of course, on Ritchie’s excavations at the site, the man in the center is wearing one of the enigmatic antler pendants from the site as, yes, a pendant. He also has a bone-handled knife at his waist, is carrying a fishing net with netsinkers, and wears a shell bead necklace (Ritchie actually thought the shell beads found at the site were associated with the later Woodland occupation). In the background, you can see a fish weir across the narrow channel between the two lakes (there is no direct evidence for weirs at the site) and fish drying racks (some post molds from the site were interpreted this way).

Always love seeing the life-size diorama of the Lamoka Lake site, representing the Archaic Period, at the New York State Museum in Albany. Based, of course, on Ritchie’s excavations at the site, the man in the center is wearing one of the enigmatic antler pendants from the site as, yes, a pendant. He also has a bone-handled knife at his waist, is carrying a fishing net with netsinkers, and wears a shell bead necklace (Ritchie actually thought the shell beads found at the site were associated with the later Woodland occupation). In the background, you can see a fish weir across the narrow channel between the two lakes (there is no direct evidence for weirs at the site) and fish drying racks (some post molds from the site were interpreted this way).

Best. Publicity Stunt. Ever. (Holy Grail category)

Visitors swamped the museum at the San Isidro Basilica in Spain after two authors published a book claiming a goblet at the basilica is the Holy Grail. It’s not clear yet if the basilica was informed of the stunt prior to publication of the book, or if they were able to raise (or start charging) admission rates before the crowds arrived. Probably not, since they were unable to cope with the demand to see the goblet and have temporarily taken it off display.

Take your pick of news reports covering the story, like this one at the Guardian.

If you need to see The Holy Grail and can’t make it to San Isidro, you can visit the Cloisters Museum in New York City and view another The Holy Grail, a.k.a. the Antioch Chalice, which is either the real Grail, or maybe a lamp. The provenience of that one seems a bit sketchy, too.