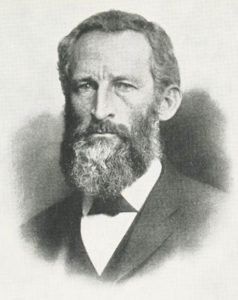

Out of a lonely and tragic childhood in Kentucky – His four younger siblings and his mother all died before he was ten years old, and his father died when he was fifteen – Charles Mitchell Smith forged a new identity and purpose for himself as a young adult, abandoning his job as a teacher (“the tedium and monotony of such a life did not appeal to him”) for a life as an archaeologist and geologist, and abandoning, at the age of 31, his birth name for that of one of his ancestors, Gerard Fowke (a cavalry officer under King Charles II who left Britain for America after Cromwell’s victory in the English Civil War).

Out of a lonely and tragic childhood in Kentucky – His four younger siblings and his mother all died before he was ten years old, and his father died when he was fifteen – Charles Mitchell Smith forged a new identity and purpose for himself as a young adult, abandoning his job as a teacher (“the tedium and monotony of such a life did not appeal to him”) for a life as an archaeologist and geologist, and abandoning, at the age of 31, his birth name for that of one of his ancestors, Gerard Fowke (a cavalry officer under King Charles II who left Britain for America after Cromwell’s victory in the English Civil War).

Fowkes’ modus operandi was simply to walk, to observe, and to dig (“in no other direction could he find equal opportunity for indulging his love of outdoor life and his desire to mingle with people who differ widely in customs, tendencies and ideals”). His method of archaeological survey consisted of walking river valleys from their headwaters to their outfall looking for sites. By the end of his career, he had walked over 100,000 miles through almost every state east of the Rockies, and several states and countries elsewhere. He worked with Warren Moorehead, the Smithsonian Institution, and the American Museum of Natural History. An account of his expeditions prior to the beginning of the Jazz Age is staggering:

· 1884 Flint Ridge, Ohio

· 1885 Mississippi, Tennessee, Ohio, Kentucky

· 1886 Pennsylvania, Illinois, Kentucky, Ohio

· 1887 Ohio, Michigan Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, New York (Niagara River gorge)

· 1888 Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky (Big Bone Lick)

· 1889 Ohio mounds excavations

· 1890 Virginia, Tennessee, New York, Indiana, Ohio

· 1891 Virginia (James River, Luray Valley, and Shenandoah River), West Virginia, Maryland, Georgia, Florida

· 1892 Columbia, South America, and the Savannah River in Kentucky, Alabama, and Tennessee

· 1893 New Jersey (studying the Trenton Gravels), Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Indiana, Ohio

· 1894, 1896, Massachusetts (studying alleged “Norsemen” sites)

· 1896-1898 Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada

· 1898 Siberia (canoeing, rather than walking, 700 miles of the Amur River as part of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition)

· 1902 Missouri (Kimmswick Mammoth/Mastodon site) and Kansas (“by means of tunnels and trenches disclosed the nature of the deposits in which was found the “Lansing Skull” 28 feet underground”)

· 1903 Missouri (caves and other sites)

· 1904 Curated the archaeological display of the St. Louis Exposition in Missouri

· 1905-1908 Missouri and Illinois

· 1909 A year of writing

· 1910 New York and Kentucky “doing literary work”

· 1911-1916 Missouri Historical Society (St. Louis area)

· 1912 Guatemala (Quirigua and other sites)

· 1914 Kansas, Nebraska

· 1917-1919 Missouri (Ozarks)

Early in his career, he became involved briefly with claims for alleged Norse archaeological sites around Cambridge, Massachusetts promoted primarily by Eben Horsford, a Harvard professor and baking powder entrepreneur. Fowke seems to have taken a moderate approach, primarily focusing on how the stone formations in Massachusetts were different from known prehistoric Native American sites.

Soon after that, he wrote one of his magnum opuses, the 760 page long Archaeological History of Ohio: The Mound Builders and Later Indians, published by the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society in 1902. This book demonstrated his wide ranging knowledge of the archaeological literature, including often lengthy quotes assembled from numerous earlier books, articles, and newspaper reports, to address two of the biggest issues of the time: Paleolithic Man and the Mound Builders. The reaction was immediate and often vituperous. One of the officials of the society that published it decried the book’s “lurid cast of sarcastic dogmatism.” (Randall 1902:160) Why such a reaction? Because Fowke rejected the concept of the Moundbuilders, an invented race of non-Native Americans who allegedly lived in America before the Indians and who built all the mounds and earthworks found throughout much of the Eastern and Midwestern United States.

Fowke calls to task those people who believed, saying:

Most publications relating to the subject, whether newspaper articles or bulky volumes, are the work of relic hunters, or persons whose curiosity is excited by something they have seen or heard, or visionaries seeking proof of a pet hypothesis – and generally finding it; careless, unskilled, and superficial observers, whose acquaintance with the science is derived mainly or in some cases entirely at second-hand, and whose statements are unsafe to rely upon no matter how honest their intentions…. Almost invariably something is taken for granted ; partial examination of a limited field becomes the basis of arbitrary deductions respecting a wide range of country; hasty surmises appear in the form of definite assertions; indications and possibilities patched together with wild guesses, are recorded as established facts. (Fowke 1902:1)

Fowke was not an ideologue –on the frankly confusing issue of alleged Paleolithic tools in the Trenton Gravels of New Jersey, he presents both sides of the argument. Although he appears to be inclined towards William Henry Holmes’ view that the supposed hand axes are more recent preforms, he withheld judgement. On the association of humans with extinct megafauna (over twenty years before the discovery at Folsom), he questioned the sketchy aspects of Koch’s account of mastodon and mammoth finds at Kimmswick, Missouri (i.e., that the Mastodon giganteus had been burned alive by people after getting stuck in the mud), but found the reported association of the bones with stone tools more convincing.

By 1902, he had over 15 years of first-hand experience with archaeological sites throughout the eastern half of the United States, which meant he could see the big picture, and easily describe regional differences in prehistoric cultures:

The great enclosures commonly called “sacred” are found between central Ohio and central Kentucky, from the panhandle of West Virginia to the lower Wabash; the garden beds are confined to Michigan and northern Indiana; the effigy mounds principally in the adjoining portions of Iowa, northern Illinois, Wisconsin and Minnesota; the great hilltop fortifications in Ohio; the pyramidal flat-topped mounds in the southern States and as far up the two principal rivers as St. Louis and Evansville.” (Fowke 1902:101)

The 65 year old Fowke entered the Jazz Age by traveling to Hawaii in 1920, beginning his expedition by consulting the staff and collections of the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, then venturing to the Island of Molokai, primarily because tourists didn’t go there. He examined and often excavated fish ponds (stone walls in inlets), taro patches, villages, temples, paved trails and alleged “sacrifice stones.” There were also stone cairns, but “The natives vigorously protested against an attempt to excavate any of these, claiming that their ancestors or members of their families are buried in them and must not be disturbed. In the dunes human skeletons are frequently exposed by the shifting of the sands by the high wind. The natives seem to have little regard for these.” (Fowke 1922:178) Despite the many finds, Fowke considered none of these to be truly prehistoric.

Returning to the mainland, he spent the next several years traversing landscapes both familiar to him and new, including a walk from Virginia north to Vermont in 1922, and a geology-focused excursion to Yellowstone, Utah and Colorado in 1923. Much of 1925 was spent in museum work in Washington D.C. He continued to travel the next several years, including a trip to excavate mounds at Marksville, Louisiana in 1926 and to Carlsbad Cavern in New Mexico in 1928.

Gerard Fowke died in 1933 in Indiana. After his death, it was written that he

delighted in exploration and up to the last year of his life was active in wresting from Nature her secrets. During his long life there were no lengthy periods of inactivity.

He was a man who loved and was much beloved by children. He spent many hours with small groups of his little friends, revealing to them the story of the rocks, the streams and the plants. (Hansford and Logan 1933:20)

References:

Fowke, Gerard

1900 Points of Difference between Norse Remains and Indian Works Most Closely Resembling Them. American Anthropologist 2(3):550-562.

1902 Archaeological History of Ohio: The Mound Builders and Later Indians. Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society, Press of Fred. J. Heer, Columbus, Ohio.

1922 Archeological Investigations I. Cave Explorations in the Ozark Region of Central Missouri, II. Cave Explorations in Other States, III. Explorations along the Missouri River Bluffs in Kansas and Nebraska, IV. Aboriginal House Mounds, V. Archeological Work in Hawaii. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 76.

1929 Gerard Fowke. Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 38(2):201-218.

Hansford, Hazel, and W.N. Logan

1933 Gerard Fowke (Charles Mitchell Smith). Proceedings of Indiana Academy of Science 43:20-23.

Randall, E.O.

1902 Archaelogical (sic) Agitation. Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 11(1):160-161

An earlier version was originally published on Jazz Age Adventurers.